Statement by Stacy A. Pedrozo CAPT, JAGC, USN U.S. Navy Military Fellow

Council on Foreign Relations

Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission

United States House of Representatives 2013

The views expressed in this testimony are the presenters personal views and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Navy or the United States Department of Defense.

Introduction

There is no doubt that China is flexing its muscles throughout Asia, sometimes acting unreasonably – its guarded, and arguably inappropriate, reaction to North Korea’s sinking of the Cheonan; its demands for an apology after a Chinese fishing boat captain was arrested for ramming into two Japanese Coast Guard vessels in the East China Sea (ECS); and its declaration of the South China Sea (SCS) as a “core interest,” on par with Taiwan and Tibet. These actions, viewed in conjunction with its increasing maritime surveillance and military exercises in the SCS and ECS, have many Asian nations on edge. Rather than increasing stability throughout the region as it gains military capability, these incidents have created more strategic mistrust and led to suspicion of China’s self-proclaimed “peaceful rise.”

China’s bold assertions regarding its maritime claims have also coincided with actions that suggest a more aggressive posture and presence in SCS, ECS, and Yellow Sea – steps which seem to have sparked a backlash of regional reactions that China may not have anticipated. My remarks will focus on certain aspects of the maritime component of China’s active defense and anti-access strategy and how that has evolved over the past year. I will also discuss how China seeks to exercise authority over its claimed maritime zones differently from the majority of the international community. Finally, I will address some of the regional consequences of that strategy and highlight what I believe are future flashpoints and sources of strategic maritime tension.

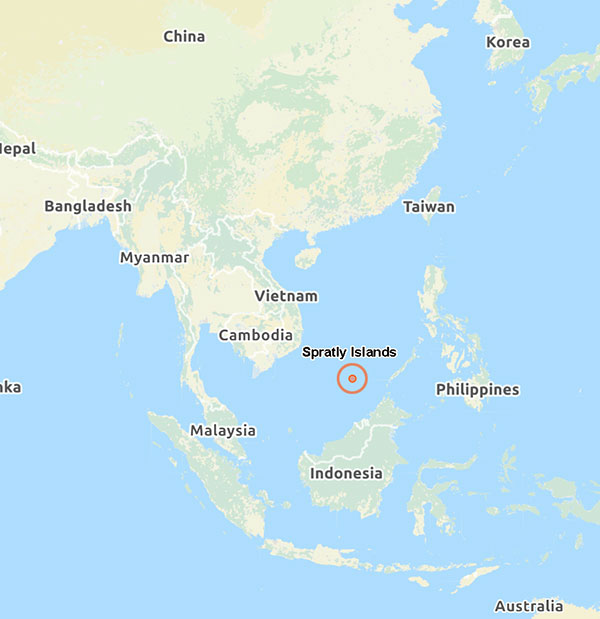

China’s Maritime Strategy

China’s active defense strategy has a maritime component that aligns with the PRC’s 1982 naval maritime plan outlined by then-Vice Chairman of the Military Commission, Liu Huaqing. This naval strategy delineated three stages. In the first stage, from 2000 to 2010, China was to establish control of waters within the first island chain that links Okinawa Prefecture, Taiwan and the Philippines. In the second stage, from 2010 to 2020, China would seek to establish control of waters within the second island chain that links the Ogasawara island chain, Guam and Indonesia. The final stage, from 2020 until 2040, China would put an end to U.S. military dominance in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, using aircraft carriers as a key component of their military force.

Recent Chinese military developments, rhetoric, and actions reflect implementation of this maritime strategy, on pace with the projections to seek control of the first island chain. Increased rhetoric and military activity over the past year includes China’s announcement that the SCS was a “core interest;” assertion and reaffirmation by Chinese diplomats and scholars that “China has indisputable sovereignty over the Spratly Islands;” unprecedented military exercises in the SCS; verbal and public protests over U.S. military activities in their claimed Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), in particular protests over carrier operations in the Yellow Sea; expansive declarations of their sovereignty over the ECS; and increased military and maritime surveillance activities in the waters off Japan. At the 18 December 2010 Shanghai Maritime Policy Symposium, a professor from the Shanghai Jiatong University Center for Oceans Law and Policy stated that “If our boats are being removed (from the ECS), naval ships and fighter jets should be deployed to the Diaoyu Islands to expel the foreign ships.” In the fall of 2010, China also announced increased fisheries patrols in the ECS. Such statements undoubtedly fuel the nationalism within Japan and China regarding their claims to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and increase regional tension.

The PRC’s active defense strategy has also been marked by their increased military capabilities, such as advanced submarines, integrated air defense systems, and the development of the DF-21D, land-based anti-ship ballistic missile. As ADM Robert Willard, Commander U.S. Pacific Command, stated in a 26 December 2010 interview, “the anti-access area denial systems, more or less, range countries, archipelagos such as Japan, the Philippines, and Vietnam, so there are many countries falling within the envelope of an A2AD capability of China. That should be concerning – we know is concerning to those countries. While it may be largely designed to assure China of its ability to affect military operations within its regional waters, it is an expanded capability that ranges beyond the first island chain and overlaps countries in the region. For that reason, it is concerning to Southeast Asia and remains concerning to the U.S.”

China’s other actions in the SCS and ECS have also facilitated the progress of their active defense strategy. ADM Willard testified before Congress in 2010 that the PLAN had increased its patrols in the SCS and “had shown an increased willingness to confront regional nations on the high seas and within contested island chains.” It was reported that in 2009 the Chinese had prepared a tactical warplan to seize control of the islands in the SCS. In July/August 2010, China staged the largest joint military exercise it has ever conducted – involving half of the vessels from all three Fleets, as well as bombers and anti-ship missiles. Then, in November 2010, China conducted an unusually transparent live-fire exercise in the SCS, employing amphibious assault ships and tanks while countering electromagnetic interference. Uncharacteristically, numerous military attaches were invited to observe the maneuvers.

There have also been several other reports of China’s increased military activities in the ECS and SCS over the past few years. One report from a Japanese national newspaper revealed that, in Febuary 2009, a Chinese nuclear submarine had crossed the first island chain in waters near Taiwan. This article also outlines other incidents in 2004 where a Chinese Han was discovered southwest of the Okinawan island of Ishigaki and another incident where the U.S. and Japan monitored a Chinese submarine making a cruise around Guam. All of these incidents symbolize that Beijing is expanding the geographic reach of its military operations. It has also been widely reported that China has drastically increased their military footprint on Hainan Island, building piers capable of berthing aircraft carriers and Jin and Kilo class submarines, which may explain their sensitivity to U.S. surveillance operations in the area. A recent article in the Jakarta Post noted that Indonesia was calling for a binding SCS Code of Conduct since “China has begun to beef up its own navy to protect key trade routes, noting that the submarine base on Hainan Island, adjacent to the SCS, houses its ballistic missile submarines -- a major component of its nuclear arsenal.” After chairing a recent meeting with ASEAN foreign ministers, Indonesian Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa said that the group needed to find another way to move the stalled SCS issue forward by engaging senior officials in working group discussions about the code of conduct.