Meet Your Military

- Details

- Hits: 3219

PHOTO: Ryan Forbes, right, a 13-year-old San Diego native diagnosed with Medulloblastoma, a form of brain cancer, and his older brother Jason eat “chow” with the Marines of Lima Battery, 3rd Battalion, 11th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, during a Make-A-Wish Foundation event aboard Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, Calif., May 13, 2014. U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Ismael OrtegaMARINE CORPS AIR GROUND COMBAT CENTER TWENTYNINE PALMS, Calif. – He stands noticeably smaller than the Marines to his right and left. Their frames fill out their camouflage utilities and flak jackets, while his looks a couple sizes too small. Make-A-Wish Foundation partnered with 11th Marine Regiment to help Forbes fulfill his wish to become a “Marine for a day.” Despite the noticeable size difference, Ryan Forbes, a 13-year-old native of San Diego, held his own with the Marines of Lima Battery, 3rd Battalion, 11th Marine Regiment. His grin from ear to ear could be seen as they joked during lunch and when describing the lifestyle of the Marines in the field. Forbes received a small taste of that lifestyle when he was made a “Marine for a day” with the battery.

PHOTO: Ryan Forbes, right, a 13-year-old San Diego native diagnosed with Medulloblastoma, a form of brain cancer, and his older brother Jason eat “chow” with the Marines of Lima Battery, 3rd Battalion, 11th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, during a Make-A-Wish Foundation event aboard Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, Calif., May 13, 2014. U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Ismael OrtegaMARINE CORPS AIR GROUND COMBAT CENTER TWENTYNINE PALMS, Calif. – He stands noticeably smaller than the Marines to his right and left. Their frames fill out their camouflage utilities and flak jackets, while his looks a couple sizes too small. Make-A-Wish Foundation partnered with 11th Marine Regiment to help Forbes fulfill his wish to become a “Marine for a day.” Despite the noticeable size difference, Ryan Forbes, a 13-year-old native of San Diego, held his own with the Marines of Lima Battery, 3rd Battalion, 11th Marine Regiment. His grin from ear to ear could be seen as they joked during lunch and when describing the lifestyle of the Marines in the field. Forbes received a small taste of that lifestyle when he was made a “Marine for a day” with the battery.

The Marine Corps coordinated with the Make-A-Wish Foundation to grant Forbes’ wish May 13. Forbes was diagnosed with medulloblastoma, a form of brain cancer in January, but he hasn’t let his current treatment hinder his enthusiasm for the military. Forbes arrived with his parents and brother in the morning, but after a short meeting and a long drive, he was seen in flak jacket and Kevlar. He talked to Marines about various weapon systems, ate a Meal, Ready-to-Eat, called orders through the radio and participated in a fire mission at the gunline. It was an eventful day that culminated with him fulfilling one of his dreams. “I came out and fired a howitzer,” said Forbes with a grin. “It shook me.” Forbes has wanted to join the military for several years. He spends time learning about the different branches, what it takes to complete recruit training and the various weapon systems. He saw some of the same weapon systems today. “I learned a lot about different guns like the 240B (machine gun) and the SAW (squad automatic weapon), and how a howitzer works,” Forbes said.

Read more: Meet Your Military: Marines Grant San Diego Youth's Wish

- Details

- Hits: 3741

PHOTO: Air Force Col. Brad Hoagland, left, and Air Force Lt. Col. Elizabeth Clay, graduates of the same Ohio high school and of the U.S. Air Force Academy, pose for a photo at the 386th Air Expeditionary Wing in Southwest Asia. Courtesy photo SOUTHWEST ASIA – Throughout life, there are people who inevitably leave lasting impressions -- an imprint on our consciousness. As examples, mentors and friends, they help us strive to be better, push harder and reach for higher goals. For Air Force Lt. Col. Elizabeth Clay, Air Force Col. Brad Hoagland made a difference in her life and career more than 28 years ago, when the two were in high school. Today, they find themselves serving together halfway around the world -- he as the vice commander of the 386th Air Expeditionary Wing and she as deputy commander of the 386th Expeditionary Maintenance Group. Clay and Hoagland grew up in the neighboring small towns of Elyria and Oberlin, Ohio, where they attended the same elementary and high schools. Hoagland, three years ahead of Clay in school, had three younger brothers, one of whom was in the same grade as Clay.

PHOTO: Air Force Col. Brad Hoagland, left, and Air Force Lt. Col. Elizabeth Clay, graduates of the same Ohio high school and of the U.S. Air Force Academy, pose for a photo at the 386th Air Expeditionary Wing in Southwest Asia. Courtesy photo SOUTHWEST ASIA – Throughout life, there are people who inevitably leave lasting impressions -- an imprint on our consciousness. As examples, mentors and friends, they help us strive to be better, push harder and reach for higher goals. For Air Force Lt. Col. Elizabeth Clay, Air Force Col. Brad Hoagland made a difference in her life and career more than 28 years ago, when the two were in high school. Today, they find themselves serving together halfway around the world -- he as the vice commander of the 386th Air Expeditionary Wing and she as deputy commander of the 386th Expeditionary Maintenance Group. Clay and Hoagland grew up in the neighboring small towns of Elyria and Oberlin, Ohio, where they attended the same elementary and high schools. Hoagland, three years ahead of Clay in school, had three younger brothers, one of whom was in the same grade as Clay.

Both were active in their high school athletics programs, with Clay playing volleyball, basketball and running track, and Hoagland winning two state championships in football during his high school years. It was during this time that the two learned the importance of working as a team, dedication and setting high goals for themselves. It was this foundation that would propel both forward in their Air Force careers. In 1986, Clay was attending the end-of-year awards ceremony for her high school and witnessed a special moment in Hoagland’s life. He had been called onto the stage at Elyria Catholic High School to be presented with his appointment to the Air Force Academy.

Read more: Meet Your Military: Hometown Friends Serve Together on Deployment

- Details

- Hits: 2977

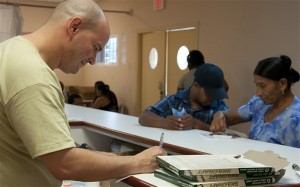

PHOTO: Air Force Lt. Col. (Dr.) Steven Acevedo, New Horizons onsite team lead and pediatrician, assists with distributing medications during a medical readiness training exercise at the Isabel Palma Polyclinic in San Antonio, Belize. Belizeans received medical care through Belizean health care workers, as well as Canadian and U.S. military care providers. U.S. Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Kali L. Gradishar PUNTA GORDA, Belize– Lt. Col. (Dr.) Steven Acevedo has enjoyed a variety of assignments in his Air Force career. For five years, he was a medical laboratory officer before going to medical school while in the Inactive Reserve. After that, he found himself as a pediatrics flight commander until he journeyed to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, followed by assignments in Lakenheath, England, and Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona. His travels continue, as he is now off to Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland in Texas for a neonatal intensive care fellowship.

PHOTO: Air Force Lt. Col. (Dr.) Steven Acevedo, New Horizons onsite team lead and pediatrician, assists with distributing medications during a medical readiness training exercise at the Isabel Palma Polyclinic in San Antonio, Belize. Belizeans received medical care through Belizean health care workers, as well as Canadian and U.S. military care providers. U.S. Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Kali L. Gradishar PUNTA GORDA, Belize– Lt. Col. (Dr.) Steven Acevedo has enjoyed a variety of assignments in his Air Force career. For five years, he was a medical laboratory officer before going to medical school while in the Inactive Reserve. After that, he found himself as a pediatrics flight commander until he journeyed to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, followed by assignments in Lakenheath, England, and Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona. His travels continue, as he is now off to Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland in Texas for a neonatal intensive care fellowship.

"I'll stay in for 20 years and retire, but I'll make sure I have a well-rounded career before it's time to move on to something else," he said. Acevedo already had been accepted to medical school before joining the military, but he said he just wasn't ready to go until he had served as a lab officer for five years. He resigned his commission as a captain to attend school at the University of Texas-Galveston, and then completed his residency at the San Antonio Military Medical Center. "It really worked out well, I think," the lieutenant colonel said. "Because I had already been a captain, I got promoted ahead of my peers, so it all catches up." A handful of assignments later, Acevedo found himself tasked as the lead for a team of medical providers during the New Horizons Belize 2014 medical readiness training exercise, in the southern Toledo district in Belize.

Read more: Meet Your Military: Medical Officer Has Varied Assignments

- Details

- Hits: 3182

PHOTO: Retired Marine Corps Gen. Charles C. Krulak, who’d served as the 31st commandant of the Marine Corps from 1995-1999 and is now president of Birmingham-Southern College in Alabama, proudly displays mementos of his service as a Marine Corps officer in his office. U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Jon Holmes BIRMINGHAM, Ala. – As a young man, Charles C. Krulak, now age 72, respected his father’s values: selflessness, moral courage and integrity. Krulak’s father, Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Victor H. Krulak, who passed away in 2008, imparted in his son the same values introduced to him as a Marine. Following in his father’s footsteps and making the transformation to become a United States Marine, the younger Krulak, who went on to become a four-star general and the Marine Corps’ 31st commandant, embodied those values. They are still a part of who he is today. “My father instilled in his three boys a solid foundation of trying to be men of character -- being selfless, having great moral courage and having integrity. [And] at the same time, taking those values and seeking to do the most good for the most people,” Krulak said. After retiring from the Marine Corps in 1999 after 35 years of military service, Krulak worked in the business world.

PHOTO: Retired Marine Corps Gen. Charles C. Krulak, who’d served as the 31st commandant of the Marine Corps from 1995-1999 and is now president of Birmingham-Southern College in Alabama, proudly displays mementos of his service as a Marine Corps officer in his office. U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Jon Holmes BIRMINGHAM, Ala. – As a young man, Charles C. Krulak, now age 72, respected his father’s values: selflessness, moral courage and integrity. Krulak’s father, Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Victor H. Krulak, who passed away in 2008, imparted in his son the same values introduced to him as a Marine. Following in his father’s footsteps and making the transformation to become a United States Marine, the younger Krulak, who went on to become a four-star general and the Marine Corps’ 31st commandant, embodied those values. They are still a part of who he is today. “My father instilled in his three boys a solid foundation of trying to be men of character -- being selfless, having great moral courage and having integrity. [And] at the same time, taking those values and seeking to do the most good for the most people,” Krulak said. After retiring from the Marine Corps in 1999 after 35 years of military service, Krulak worked in the business world.

In March 2011, he was selected to become president of Birmingham-Southern College in Alabama -- a position he says is one of the most challenging of his life. Mismanagement and a growing debt foreshadowed the college’s future. Budget cuts cost students their educational programs and professors their jobs. Dropping enrollment, a demoralized faculty and a community that lost confidence in the school posed additional problems making Birmingham-Southern College’s future uncertain. One of Krulak’s first decisions as the college’s new president was to refuse a salary. “They were pretty surprised when I did that,” he said. He also turned down the university vehicle and even lived in a dorm instead of the Birmingham-Southern College President’s house. “Why turn down the salary?” Krulak asked. “Because of the sacrifice everyone else had gone through. If all of the sudden I came in and had this salary and drove around in a college car and lived in the house of the president, I wouldn’t be doing what all Marines do -- setting the example.” Krulak continued that example by visiting every classroom on campus and meeting with the faculty, staff and students.

Read more: Meet Your Military: Former Marine Corps Chief Lives Father's Values

- Details

- Hits: 3573

PHOTO: Army 1st Lt. Jamie Mueller at work at Forward Operating Base Spin Boldak, Afghanistan, April 30, 2014. U.S. Army photo FORWARD OPERATING BASE SPIN BOLDAK – A U.S. Army medical officer saved an Albanian soldier’s life last month thanks to a medical exchange program here. During a routine procedure, 1st Lt. Jamie Mueller, a physician assistant with 4th Infantry Division’s 4th Special Troops Battalion, 4th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, noticed a troubling growth on her patient’s back. Mueller consulted with Army Maj. (Dr.) Michael Rossi here and with other physicians throughout Afghanistan and Germany, and they determined the soldier had cancer and needed immediate surgery. Rossi credited Mueller’s professionalism and competence as the catalyst for getting the soldier the care he needed. “She was able to gain their confidence,” he said. “As a result, they were able to find the cancer.” That confidence Rossi added, was gained through Mueller’s hard work.

PHOTO: Army 1st Lt. Jamie Mueller at work at Forward Operating Base Spin Boldak, Afghanistan, April 30, 2014. U.S. Army photo FORWARD OPERATING BASE SPIN BOLDAK – A U.S. Army medical officer saved an Albanian soldier’s life last month thanks to a medical exchange program here. During a routine procedure, 1st Lt. Jamie Mueller, a physician assistant with 4th Infantry Division’s 4th Special Troops Battalion, 4th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, noticed a troubling growth on her patient’s back. Mueller consulted with Army Maj. (Dr.) Michael Rossi here and with other physicians throughout Afghanistan and Germany, and they determined the soldier had cancer and needed immediate surgery. Rossi credited Mueller’s professionalism and competence as the catalyst for getting the soldier the care he needed. “She was able to gain their confidence,” he said. “As a result, they were able to find the cancer.” That confidence Rossi added, was gained through Mueller’s hard work.

When Mueller arrived here in February, a 12-foot wall separated the coalition forces. Though a physician assistant typically works directly with a supervising doctor, Mueller found herself as the only medical professional at the clinic. Shortly after she arrived, Mueller and her team were functioning at a high level and had begun to conduct medical exchanges with their NATO partners. “I’m just an old medic that went to [medical] school,” Rossi said. She’s the one that makes things happen. Before she got here the Albanians were on one [base], and we were on another.” Within weeks of beginning the medical exchanges, the U.S. and Albanian forces were regularly eating meals together in the American dining facility. Rossi said the crowd at meal time is getting bigger and bigger as the partnership grows.

Read more: Meet Your Military: Physician Assistant Saves Lives, Builds Bonds