- Details

- Hits: 1489

By Stephen T. Ziadie − August 31, 2021

JOINT BASE PEARL HARBOR-HICKAM, Hawaii – I took delivery of my overseas household goods shipment Sept. 10, 2001. The next day, Sept. 11, was my first full day in the office at my new assignment at Seymour Johnson AFB, North Carolina.

It was also our squadron physical training day. We completed a grueling round of strength exercises capped off with a two-mile run and the two-minute shower, change into battle dress uniforms, and then back to the squadron drill.

- Details

- Hits: 1327

By Stephen T. Ziadie - August 31, 2021

JOINT BASE SAN ANTONIO-LACKLAND, Texas – For years after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Linda Alcala wouldn’t use the restroom at the Pentagon without formulating a plan.

“What should I do if the alarm goes off? Where’s the nearest exit? How quickly can I get to my gas mask?” she would ask herself.

In 2001, Alcala was an accounting office manager at Bolling Air Force Base in Washington, D.C. She was printing reports ahead of her scheduled meeting at the Pentagon the morning of Sept. 11. A paper jam delayed her enough that she missed her bus to the meeting.

Had she been a passenger on the bus, she would have been dropped off minutes before flight 77 crashed into the west side of the Pentagon near the escalator to her fourth-floor meeting.

After the plane hit the Pentagon, Alcala spent the next several hours sheltered in a bathroom, desperately trying to reach her son and other family members to let them know she was safe at Bolling, and not at the Pentagon.

- Details

- Hits: 1842

By Thomas Brading - September 2, 2021 − FORT BELVOIR, Va. — Two decades ago as the nation reeled from the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, a unique team of search and rescue Soldiers put their training to work at the Pentagon when they were needed the most.

The effects of that Tuesday morning left a lasting legacy on the Army’s Military District of Washington Engineer Company. Years later, the unit was renamed the 911th Technical Rescue Engineer Company for its efforts that day.

Read more: 20 years later: Search and rescue Soldiers reflect on 9/11

- Details

- Hits: 1346

Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 2021- SupportOurTroops.Org was privileged to provide at no cost, including delivery, $338,000 of requested PPE to the active duty servicemembers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. 61,152 8 oz. plastic bottles of gel hand sanitizer were delivered by the SOT Team to the base for servicemembers and families. A full tractor-trailer load of care package goods.

Read more: Fort Huachuca Receives $338,000 of Free PPE from SupportOurTroops.Org

- Details

- Hits: 1359

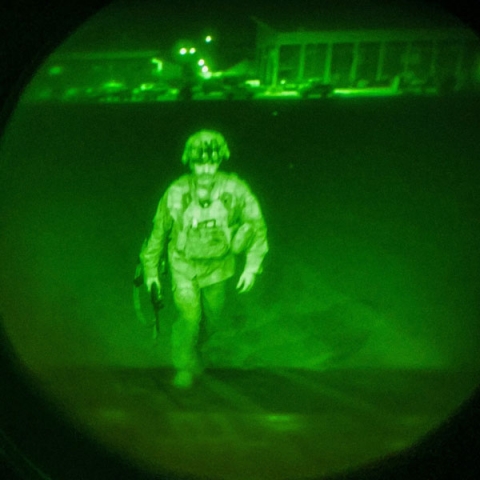

Kabul, Afghanistan, August 30, 2021 - U.S. Central Command announced early this morning Eastern Time that Major General Chris Donahue, commander of the U.S. Army 82nd Airborne Division, XVIII Airborne Corps, is the final American service member to depart Afghanistan and that his departure closes the U.S. mission to evacuate American citizens, Afghan Special Immigrant Visa applicants, and vulnerable Afghans. He is pictured here as he boards a C-17 cargo plane at the Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, Afghanistan. Photo by Master Sgt. Alex Burnett.

- Details

- Hits: 1484

August 2021- SupportOurTroops.Org was privileged to recently provide at no cost, including delivery, $79,068 of Biofreeze® Pain Relief Muscle Balm 3 oz gel tubes to the active duty military servicemembers at Fort Drum New York. 6,600 tubes! America is a beautiful country full of great and generous people and companies.

FORT DRUM, N.Y. – U.S. Army Sgt. Klayton McCallum, a combat medic with the New York National Guard’s 2nd Battalion, 108th Infantry Regiment, navigates a barbed wire obstacle during the 10th Mountain Division Expert Field Medical Badge assessment at Fort Drum, N.Y., May 20, 2021.

Photo by Sgt. 1st Class Warren W. Wright Jr., New York National Guard.

Veterans can learn more about alternative pain management here.

Read more: $79,068 of Pain Relief Muscle Balm to Fort Drum, NY

- C-17 CARRYING PASSENGERS OUT OF AFGHANISTAN

- Alabama Abounds with the American Spirit and the American Way!

- Fort Bragg Receives $196,784.64 of Free PPE from SupportOurTroops.Org!

- $39,534 of Pain Relief Muscle Balm to Fort Campbell, Kentucky

- $336,183.12 of PPE protection to Joint Base Lewis-McChord from SupportOurTroops.Org

- Tennessee Guard Scores Biofreeze!